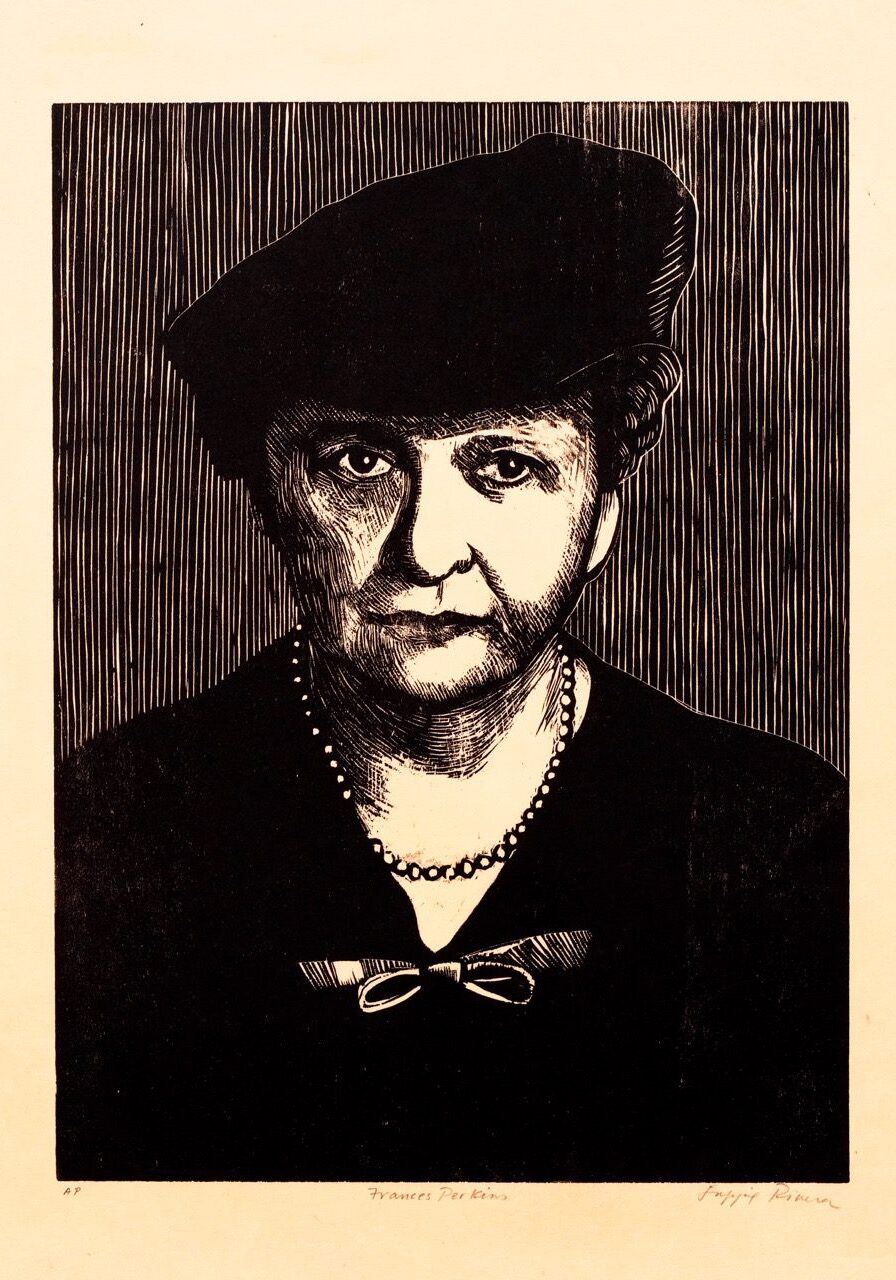

Look Again: Portraits of Daring Women

Loveland Museum, Loveland, Colorado

December 7, 2025 - April 5, 2026

This ongoing portfolio of woodcut and collage portraits was originally inspired by the New York Times “Overlooked” series, which since March of 2018 has been sharing the stories of remarkable people who were overlooked by the NY Times obituaries in the past.

To further illuminate their lives and legacies, each of my portraits is accompanied by a portrait poem, written by a woman poet. The poets created their pieces in response to both the women’s stories and to the portraits.

Meteorology

for Nella

A pale sky swallows a dark cloud,

spits

and

I am

conceived never

white

bright

black

“down”

Dane

Indian

Caribbean

American

enough never

writer

woman

fighter

white enough

never.

Dixie’s contradiction:

sin without contrition,

yellow never gold,

silver never sterling,

the coveted lining?

never, only thinning shell

veined with fractures, cracks,

quake my bones,

fever the marrow,

never fitting, never splitting

always shorn, torn,

never passing

always contrasting

the criteria.

Behold me:

the eternally stifled, toiling

beneath a battered horizon,

the flanking gray,

neither cloud nor sky, though

brewing morass asunder,

thunder holding its breath,

lightning poised with

clenched teeth,

bruised the skin

of the wind,

the cacophonous quiet, kept

never calm,

storm perfect.

Tamara J. Madison

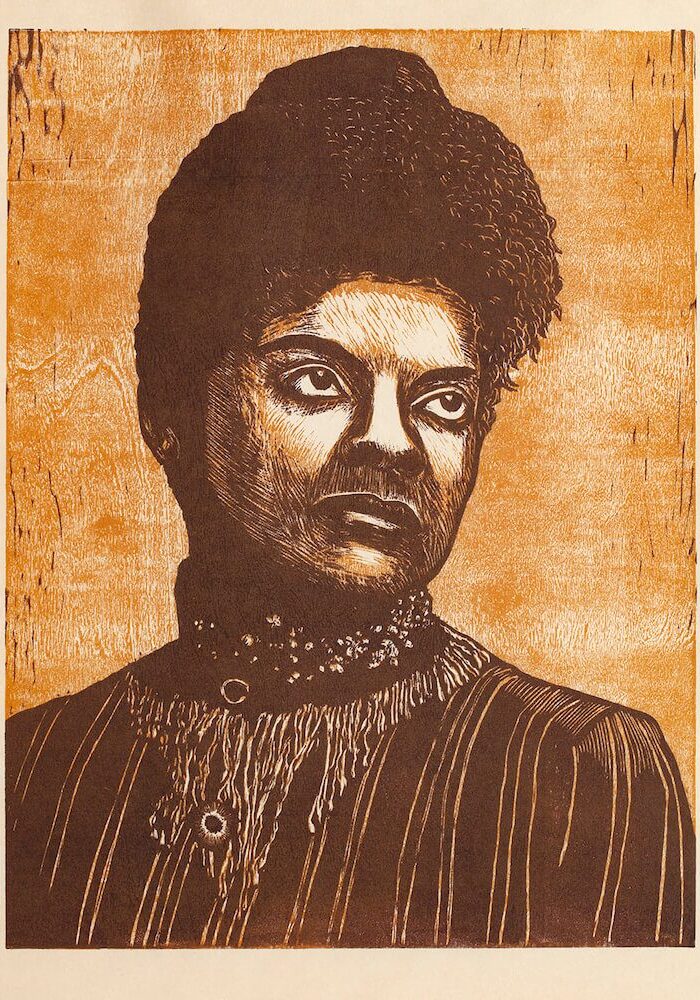

IDA

Too many nooses snug

against black necks⎯

men limp & motionless, dark

pillars against horizon. You

took up the pen, staunch,

relentless, sounded the alarm

of injustice. Small in stature,

your voice boomed⎯

phrases from the pages

you wrote ignited fear,

white men threatened

by a black woman’s rage.

How quick the wildfire.

Unflinching, you tucked

pistol in skirt pocket,

gritted teeth, somehow

fearless after mobs

strung up your brothers,

burned your press⎯

gold flames, melted metal.

You fought as only a woman

can fight, thread of tenderness

pulled taut through every violence.

You conjured wings, saying

I would gather my race in my arms

& fly away with them.

Rage Hezekiah

Our Women’s World

Melody S. Gee

Dual double my grandmother

and Qiu Jin died one

hundred years apart

Sun and moon have no light left, earth is dark,

born girls bound feet unbound

eventually two

arranged marriages two separate revolutions

the country collapses all

century

Our women’s world is sunk so deep, who can help us?

Jewelry sold to pay this trip across the seas,

My grandmother paid passage with gold too

out of the storm of a hundred

flowers Cut off from my family I leave my native land.

the revolutionary left her children for Japan

feminist heroes the government loves

a rebellion story after regaining hold

Unbinding my feet I clean out a thousand years of poison,

Qiu Jin studied in men’s clothes

My grandmother canned tomatoes

With heated heart arouse all women’s spirits.

on unbound feet the body

learns to stand on broken bones

Alas, this delicate kerchief here, Qiu Jin falls be

headed defiant my grandmother walks a new country

without the words she gives to me

Is half stained with blood, and half with tears.

https://thechinaproject.com/2020/07/15/a-revolutionary-against-empire-and-patriarchy-the-

execution-of-qiu-jin/

https://www.asymptotejournal.com/poetry/qiu-jin-five-poems/

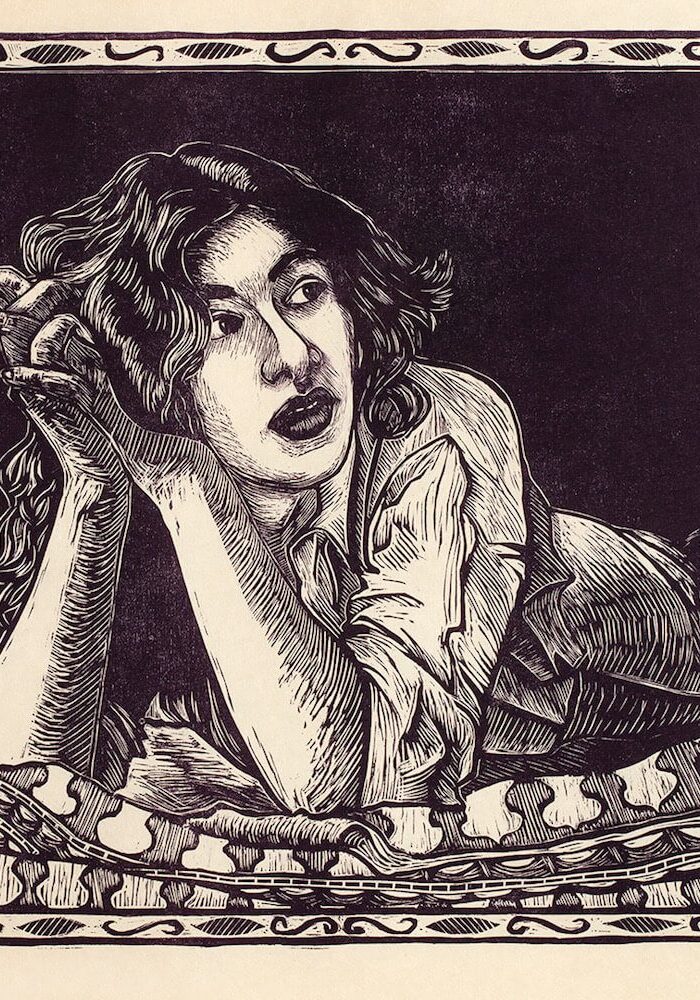

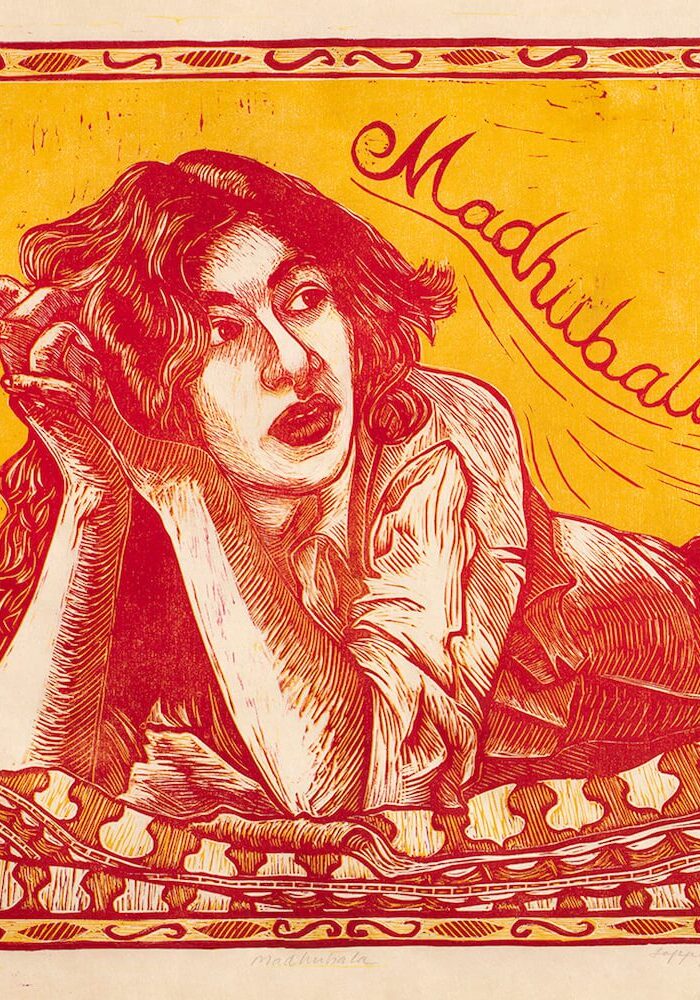

Madhubala

already half gone

making up the heart's insufficiency

in bright, soft black

smile like color

as if the moonlight were real

black hair blushing

you ran here

on bare feet, a Bombay child

shoulders dancing

now pretend to rest

poise your chin in readiness

as if illumination

were your name

as if you were a spectral song

on gold water

as if this frame

and every flickering frame

made you full

Libby Maxey

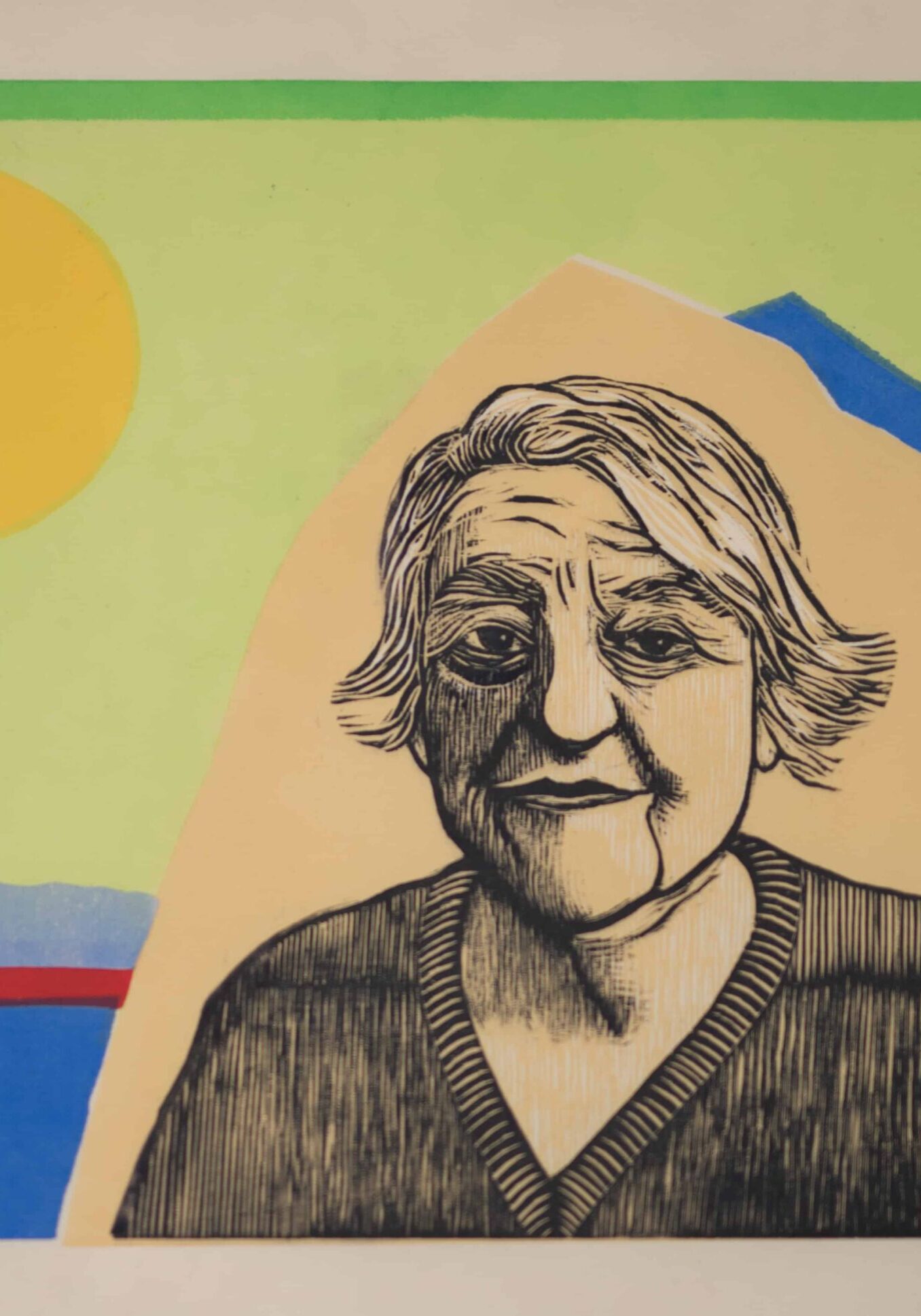

Etel Adnan

You said “identity is your prison” and roamed the world borderless, art your harbor. You said “poets transcend language,” and languages flowed in you like a river. A polyglot exile who understood that all is translation, you let the wind enter your porous skin, shift the shimmering light into new constellations. A distillation. In motion you sank roots and sang “we’re rhythms,” extending your hands for the world to fall into your open palms. Algeria, Vietnam, Beirut; the gasps of Arab nations trying to free themselves from the clutches of tyrants broke your heart. You were of the pen and brush; with them you fashioned order, merciful, out of the unbearable. “The dream has no walls.” You called it love.

I, daughter of the nation-state carved out by cold-blooded giants from the empire that saw your beginnings, bow to the tapestry you wove out of the many threads of your life. The languages that inhabit me refuse to talk to each other, the threads “disappear in the wanderings.”

Therese Chehade

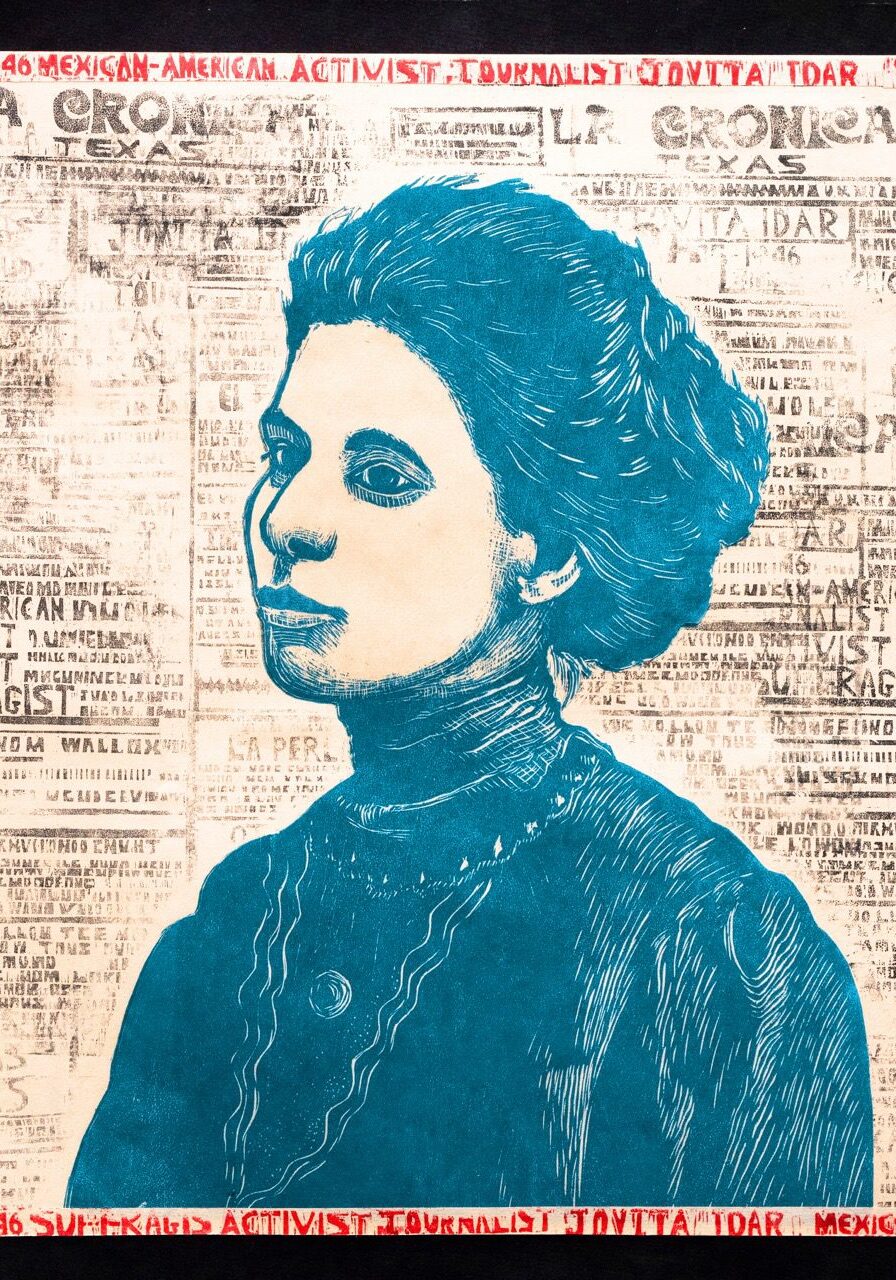

Inviting the Broad Horizons

—for Jovita Idár, 1885-1946

The border descended like a scythe

just forty years before your birth;

mountains, homes, and trees still hold

their Spanish names—montañas, casas, árboles.

But in dirt-floor schools, you witness

textbooks teaching children to feel like strangers

in their homeland. You feel it too

with the knowledge of intimidations,

lack of resources, lynching.

They mean to bury your voices in sand.

So you as Astraea, goddess of justice,

puncture the blindfolds with starlight

then illumine the broad horizons.

You as Ave Negra dip your wings

into wells of ink mixed with weeping and ash

then write your message in the sky

for los habitantes Mexicanos de Texas,

for la mujer moderna, for la raza.

You, Jovita Idár, write in La Crónica,

and later in El Progresso,

and then in your own press: Evolución.

From cacophony, you assemble

one sound at a time until

your steadfast voice is a ringing bell

whose strength emboldens strength, until

your endeavors live in the air, your words

traveling generations ahead to say,

When you educate a woman, you educate a family.

You welcome las mujeres and las niñas

into la Liga Femenil Mexicanista.

And when la Revolución draws near,

you pass through the border

to heal the wounded fighting for their democracy.

Your heart erupts for them. You promise

to always stand in the doorway.

We feel your presence even now, your voice.

When officers came with sledgehammers

to destroy the press, you refused to move.

You said, No. I’m standing here.

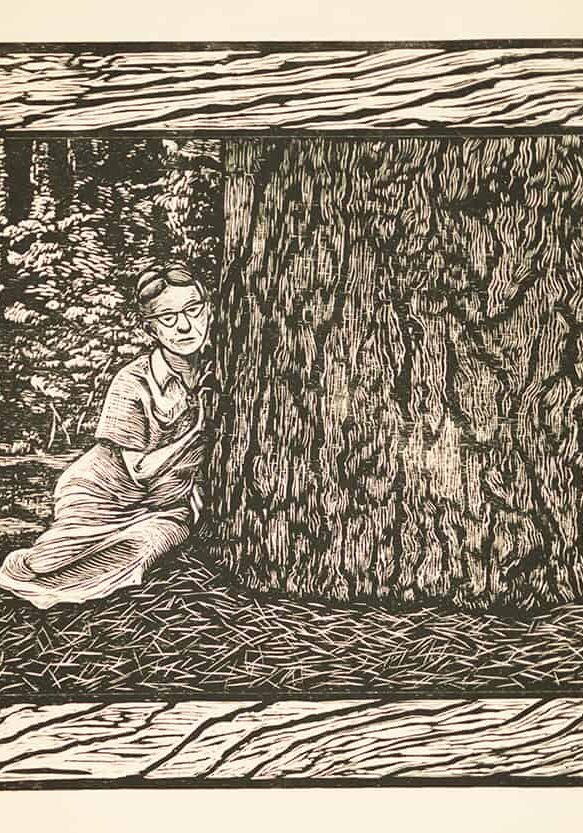

The Longleaf Pine Woman

—Caroline Dormon (1888-1971)

I have listened to the trees talk, later

than I longed. My ear was its own

stethoscope, I felt the pulse, I heard

the waters flow through xylem

in vertical rivers, emptying

into fireworks of deep-green

needles. Need grows deeper.

For so long, I’ve collected life

histories. I’ve walked the land

through Louisiana, parish to parish,

raised seedlings, felt the fire

of their roman candles. A longing

carried me as I toiled to save them.

It can take a long century to reach

the forest canopy where sprays

of needles watch the clouds

and stars. And no bed is finer

than a needled floor, no resting

place more welcoming, far

below the oval, open crowns.

Being resinous, pitch and gum

can save them from fire, and

skeletons of snag may recover.

But from the blade? For this I walked.

—Sharon Tracey

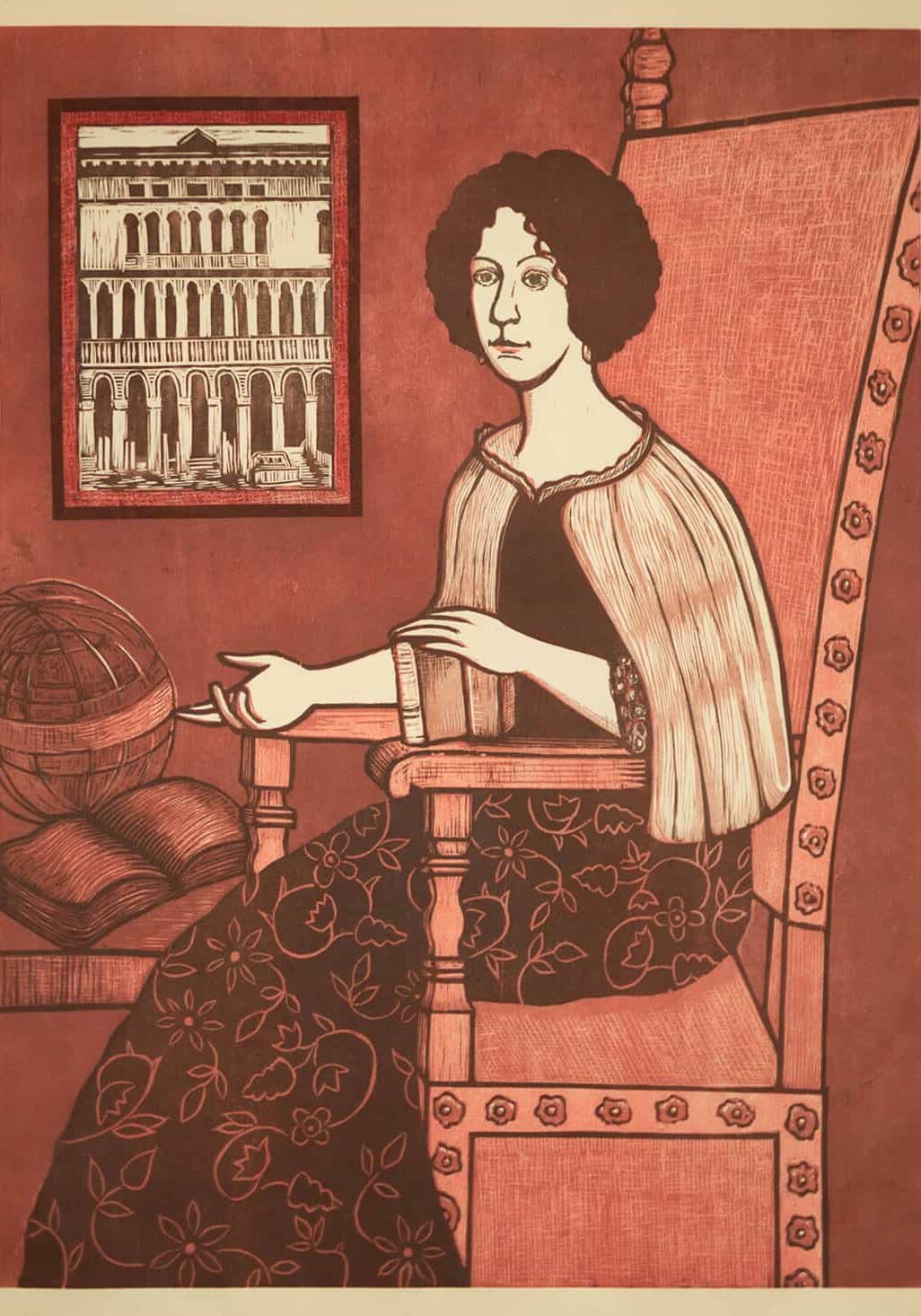

The Seven-Language Oracle Confesses

by Jennifer Martelli

for Elena Cornaro Piscopia, (1646-1684), Doctor of Philosophy

All day, on the verge of my seventh language,

I break things: the gun metal globe, the spine

of Sappho’s translated fragments, which will not

exist for two hundred more years. She wrote:

In some future time, someone will think of you.

The stiff linen pages slice my fingertips. I leave

peonies of blood on all I touch. Yet, I’m glad

for this tongue. Oraculum Septilingue, they’ll call me.

Last night, I dreamt the collective dream of Venetians:

gold snakes and blood-red wombs etched into stone

columns of the university. The sultry air steaming off

the canal slithered into my maroon dreamscape. Someday,

I’ll be a crater on Venus. Oblate, devotee, on the verge

of love, you won’t even need a convex lens to see me.

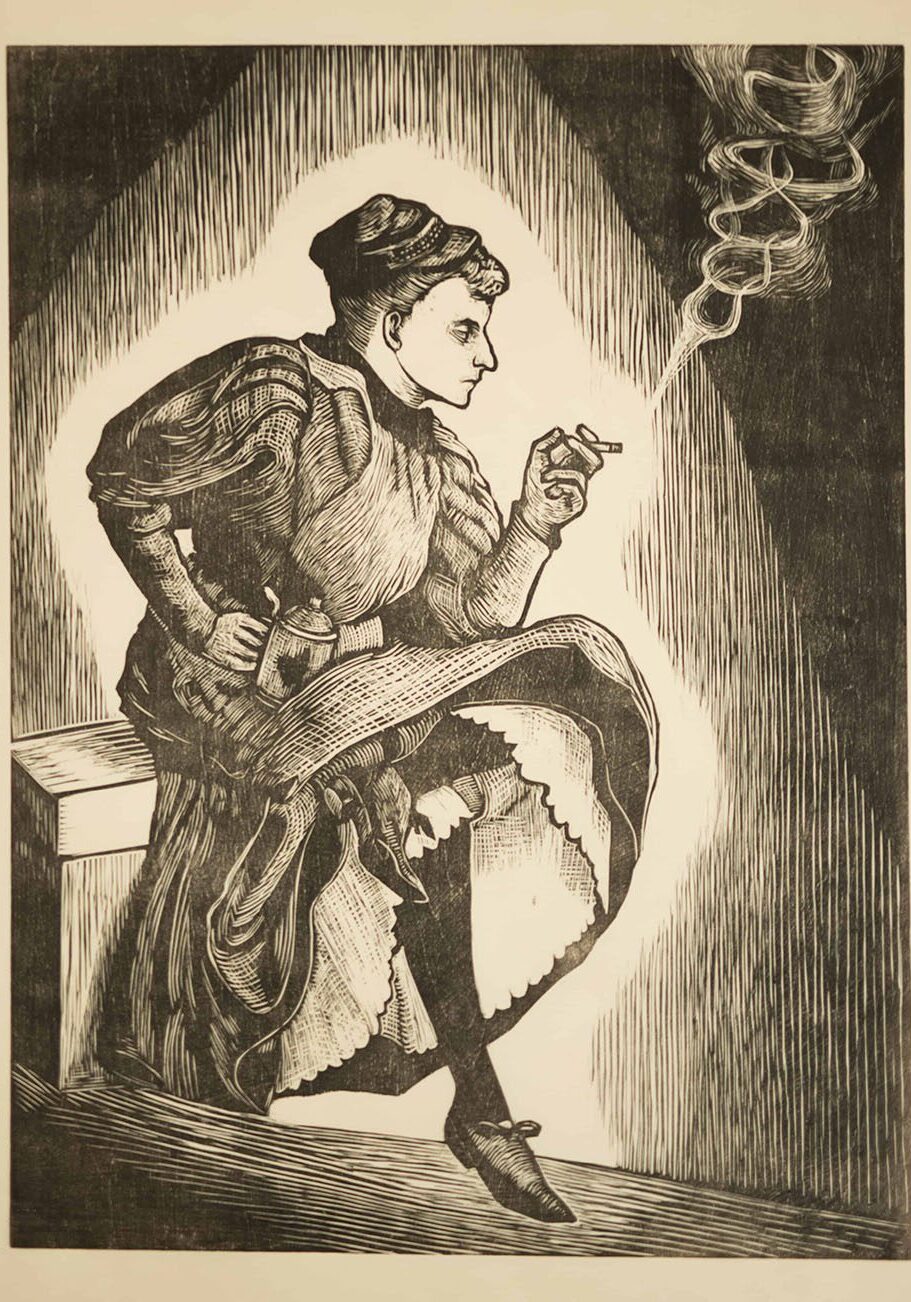

A Woman’s Eye

by Sharon Tracey

—for Frances Benjamin Johnston (1864—1952)

Born during the Civil War, here you are

seated in profile, just like your own

self-portrait you called The New Woman—

cigarette smoking, beer stein in hand,

petticoat showing, legs crossed man-style,

illuminated, full of dreaming and drive

the images to come far reaching—

portraits of five presidents, diplomats,

miners, black students at the new

universities in Hampton and Tuskegee,

elaborate gardens, coal fields, and caves.

Your camera then turned to the bricks

and old buildings across the South,

many soon to be lost. A life’s work

of lucid photographs, detailed in shafts

of light, cracks of dark—accumulating

like leaves falling from trees, each

a fleeting history, each wielding more

than its own weight—twenty-thousand

prints and thousands of glass and film

negatives archived at the Library of Congress—

time compressed, composed in a woman’s eye.

—Sharon Tracey 10/15/22

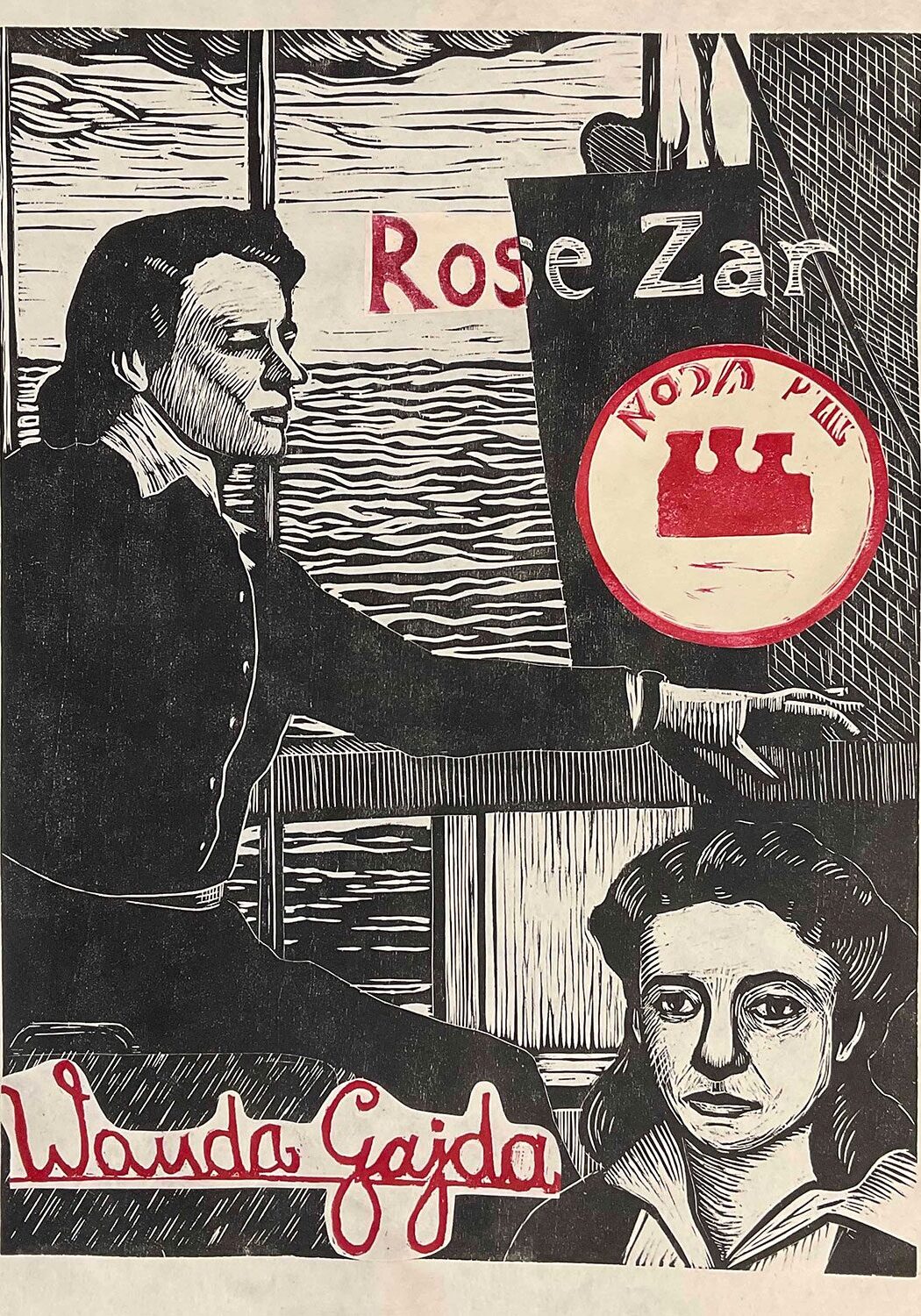

Rose Zar, Hiding in Plain Sight

Look again.

Can you see who I am?

Do I give you even a moment's pause,

one more survivor of the Holocaust?

Rose ~ the name I took when I came

to this immigrant gathering place,

my husband and I, lone survivors,

haunted by our terrifying past.

Ruszka ~ my childhood name

echoing through our Polish home:

love...learning...laughter...

that world is gone forever.

Rushkala ~ my father called me,

he who prepared me, branded me

with the duty and courage to survive,

exiled from our ghetto grave.

Wanda ~ Arayan Catholic forged papers,

I was hunted, always afraid,

held in the mouth of the wolf;

how hard it was never showing fear!

Shoshana ~ Hebrew Zionist rose

happily singing of a promised land;

only three of our Youth Group lived.

Forty-two died. Israel was never home.

Hiding in plain sight, remembering

always, inside: I am a Jew,

even as they shrieked: “Alle Juden Raus!”

Prey of hate, fear helped me focus.

Look again.

Do you see who I am?

Joy is a stranger to me.

My life is my grief.

Nancy Collins-Warner

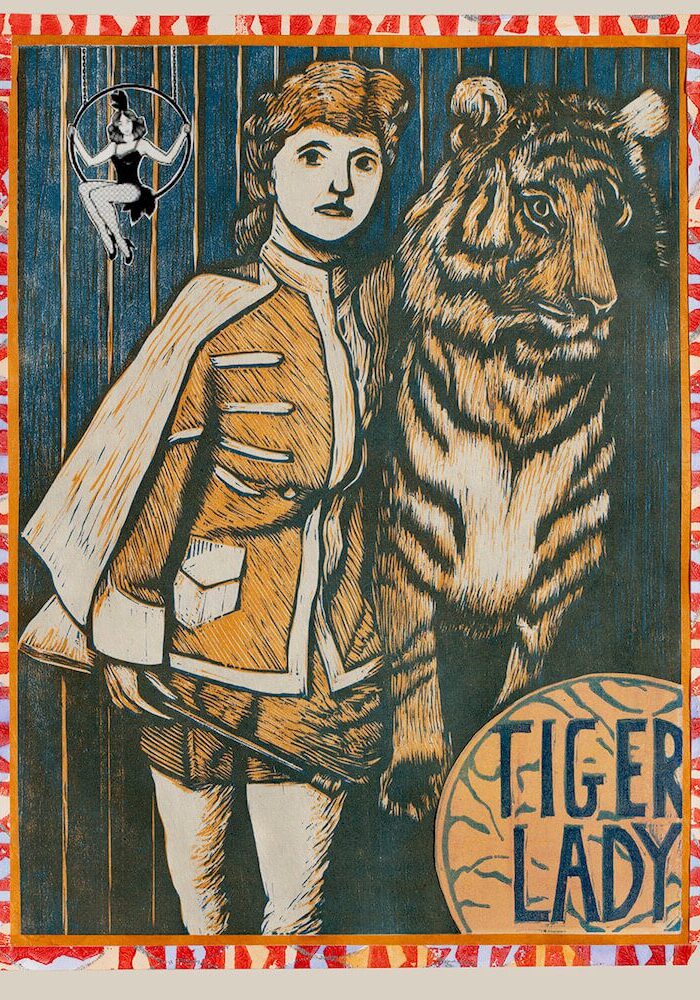

Tiger Lady

for Mabel Stark, born Mary Ann Haynie, 1888-1968

Just past twenty when she first walked by that royal Bengal—King—

and before long she had the whole streak suspended, walking thin lines

at her command, jumping through blazing hoops, assembling a wild pyramid

of striped power, held in place by the promise of raw meat and her stick.

Maybe she thought of her dead father and mother, and the stepfather

she escaped. She wanted to quit hoochie-coochie dancing—her bared belly,

twisting her body round a pole—and nursing, that other women’s work,

without thrill, the sap of taking care, spotlight on the sick and not the vital

growl. It makes sense she’d want to cast off fear, wield the whip,

hold back what would maul her if given half a chance.

She said I love these cats as a mother loves her children. Her tigers

raised under a tent, behind iron, made to pounce on pedestals and pose.

That is one kind of caring, all whip-smart and firm, demanding

arrangement, with the coo and the strike. What other fierce things

was she snapping into shape, inside her mind, prowling the edges of her

caged heart? As a woman, she would have known that balancing act,

what it is to be disciplined for baring the teeth we are born with.

Nearly eighty, at the close of her career of cats, she felt blank

as the bullets in her warning gun without them, downed

sedatives once she was no longer allowed to wrestle with tigers.

She leapt with them, through a kind of fire, when she entered their cages,

when she stepped to the middle of the ring. What conflagration

was she stoking with her little cape, her metal gloves? The crowd roared

over a circus backdrop reeking of peanuts, sweat, and rancid hay,

while teeth tore away a breast, ligaments, bestowed her with 700 stitches,

blood pouring into the chalices of her 26-inch boots. The only way she felt

alive, each tooth undoing old wounds fast as a flick of flame. She admitted

there was no such thing as tame. She placed her face between the open jaws.

Rebecca Hart Olander

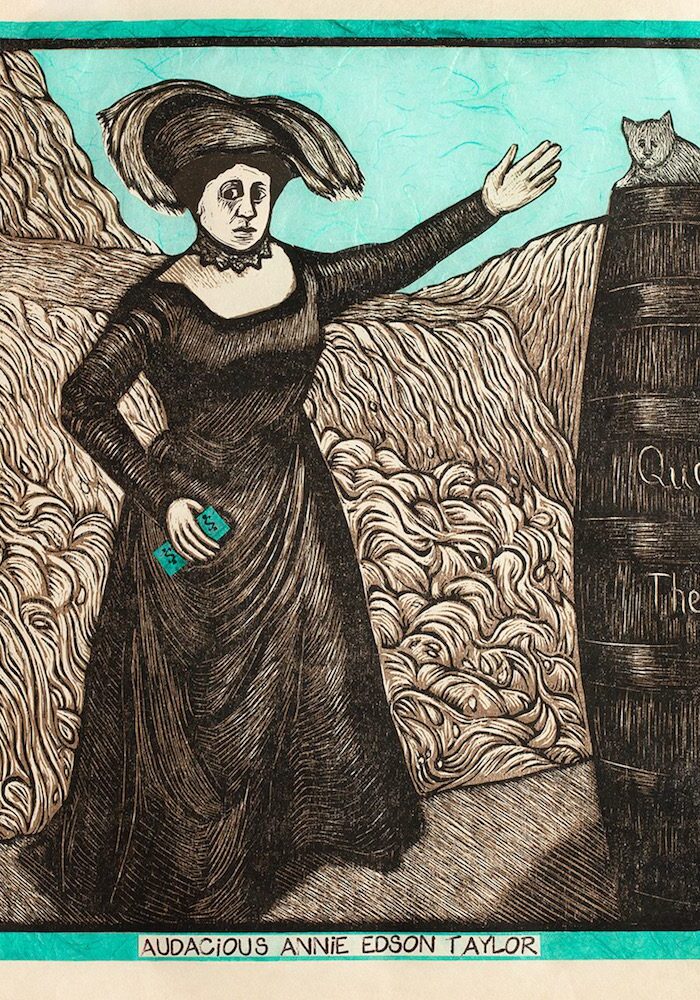

Annie on the Edge

In your dark dress, you stand

beside the dark capsule of your design,

weighted to give gravity a hand

when you fall over Niagara Falls.

Pledge of bravery in

your posture. You lie about your age.

When you climb inside the barrel,

your skirt forms a padded circle.

The harness. Then the lid. The wide

river takes over.

At the brink there is a pause

and you pause.

In twenty minutes, the journey

ends. You are the first ever, the first

woman to survive the fall. The key

to your livelihood. Your survival.

The adventure so unlikely,

its desperation.

For a brief time, acclaim. Money. Brief.

You circle back to the watery

riot of the falls. At the end of your life,

pamphlets and potions and magic tricks

for tourists like us.

Jean Blakeman

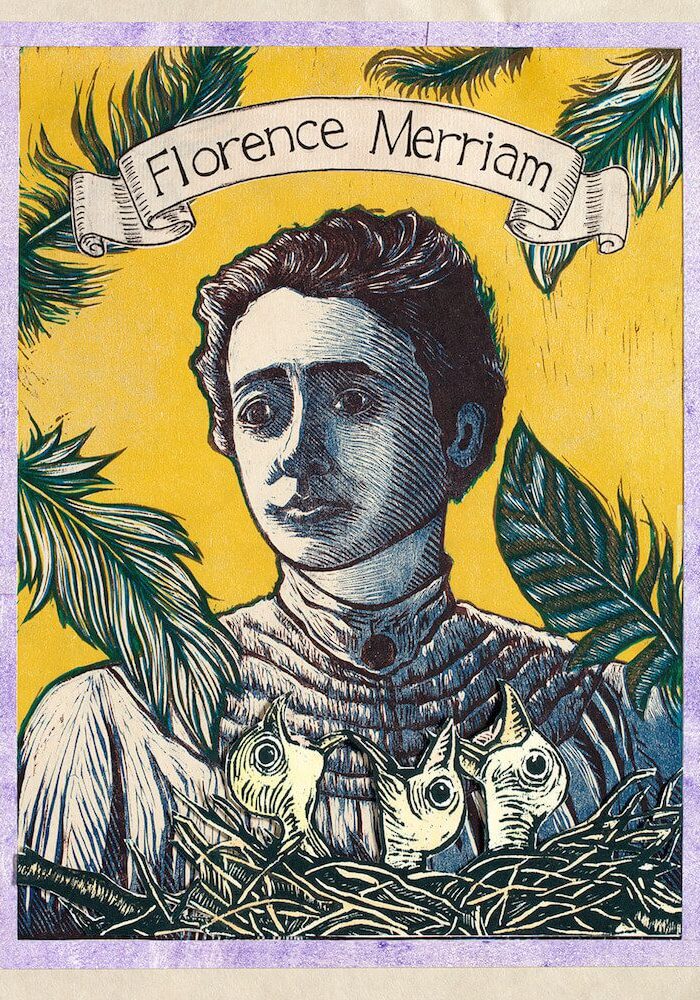

Wings

“We’ll take the girls afield, and let them get acquainted with the

birds.

Then of inborn necessity, they will wear feathers never more.”

Florence Merriam Bailey

Birds Through an Opera Glass is what she called the book

she wrote at 26, upending the practice of shooting

birds to study them. Then there were the ladies of marvelous

plumed adornment, buying birds to death: 5 million/year

multiplied by the songs no one ever heard.

Not all of us are equipped with a driving passion, not all

driving passions are powered by love. Florence

said to the women, bring your opera glasses for our walk,

knowing once you watch a chickadee watch you,

you’re different. Maybe tuberculosis taught her something

we can’t learn an easy way, about constriction, and how anyway

to let the heart fly into the world. Think of it: 5 million x the years

since she wrote her book equals how many seeds carried

to new fields? How much pollination of the flowers of those seeds,

and honey made in the trees her saved birds planted?

Adin Thayer

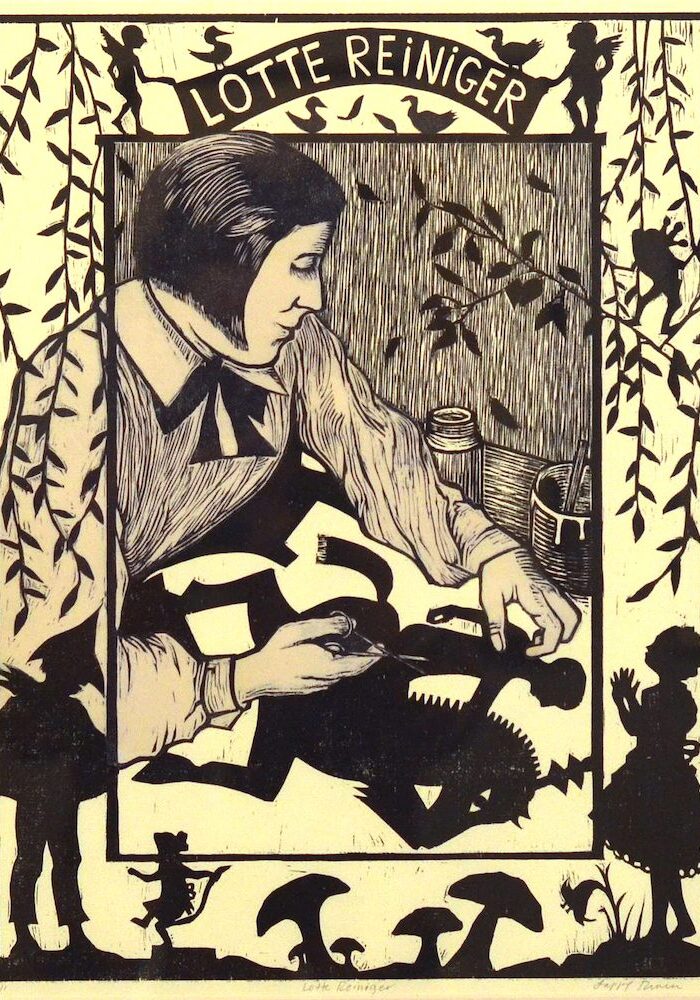

Hinged Dreams

“I now have one desire — to make films.”

Lotte Reiniger

A sorcerer thin as a rake with gnarled knuckles shakes them

at Prince Achmed as his horse gallops

across a shivering moon. A princess bird descends by an opal

lake and steps from her owl-soft plumage. Lotte’s life

is a story of stories told through thinly hammered lead.

Before leaving the land of the Fuhrer, her gifted fingers

woke, and a gift’s desire was the fuel for their burning speed.

These stories flew from the small scissors

in her hand and step by step she coaxed them

across an under-lit screen, still-shot by still-shot. By each

the world’s treasury of magic grew and the mind

of childhood was nourished. As is the life of any pioneer, hers

was a series of obstacles, money, loss, the post-war taste

for realism, and steadily she scissored through them,

and who would not, who found within herself so rare a gift,

to imagine metal into motion, to snip a crow into dipping across

the moon of her imagination or a princess into slumping

down for a century of sleep?

Adin Thayer

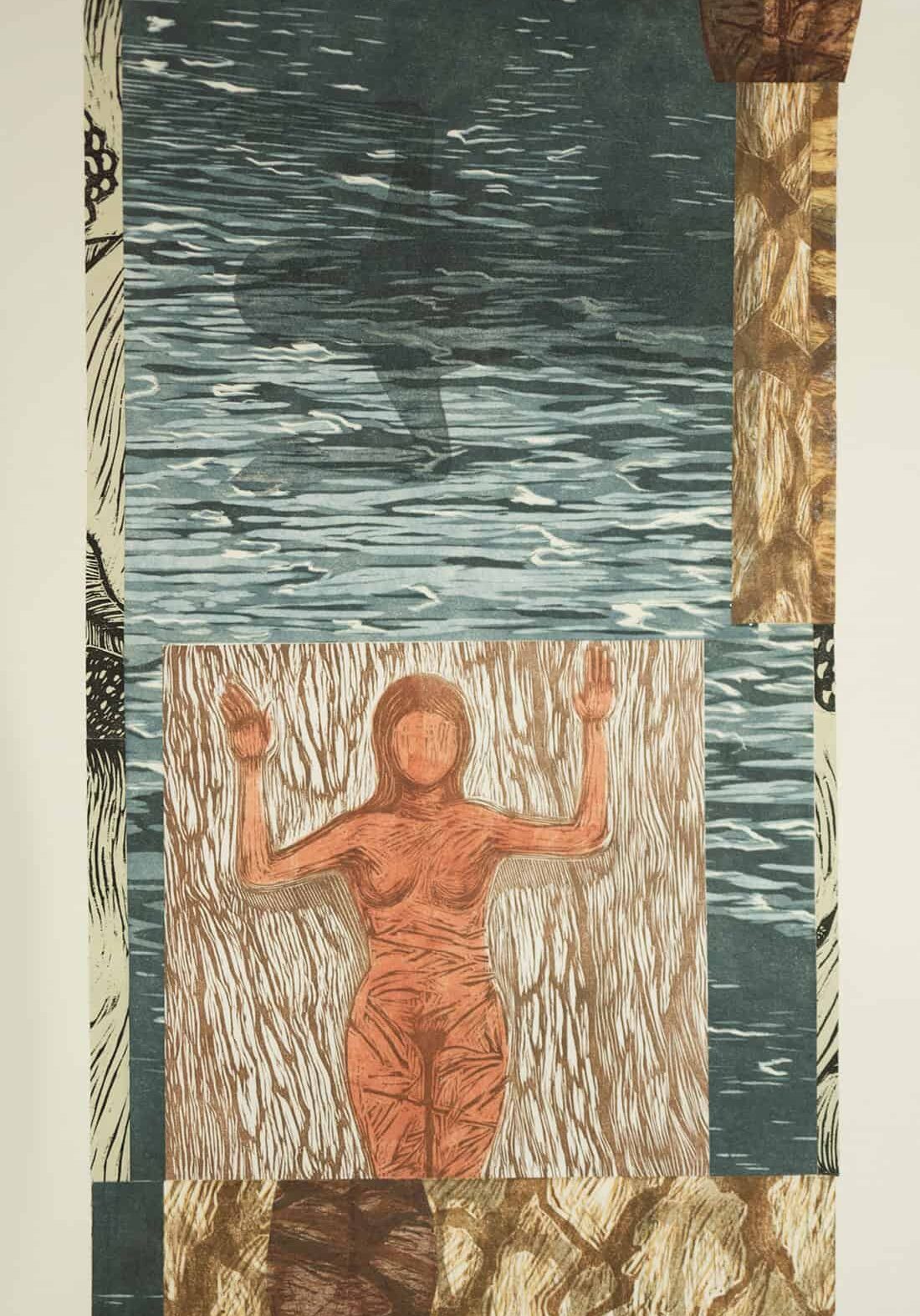

Silueta

—for Ana Mendieta

The corpus—female body as icon—

its own landscape

was always your life’s work.

Silueta you called them—

dressed in weeds and white flowers, blots of blood

mixed with dirt. Apparitions thatched

and as matted as shocks

of wild hair. One

you laid to rest in an open stone

tomb, legs slender as pipettes

and translucent as veins. One

you carved in a dry streambed. One

you torched with red fire.

Some you made with your own

skin as canvas: a coat of mud, the grit of sand,

the end product of many things.

Raw and exposed, you are brave.

There are multitudes.

An exile seeks roots.

With a camera you tried to save them—

echoes and traces, afterimages

and impermanent marks. Penumbrae

caught between light and dark

in silver gelatin

the body—a landscape of the visible—

but also a figuration

of what lies

in shrouds of earth.

Sharon Tracey

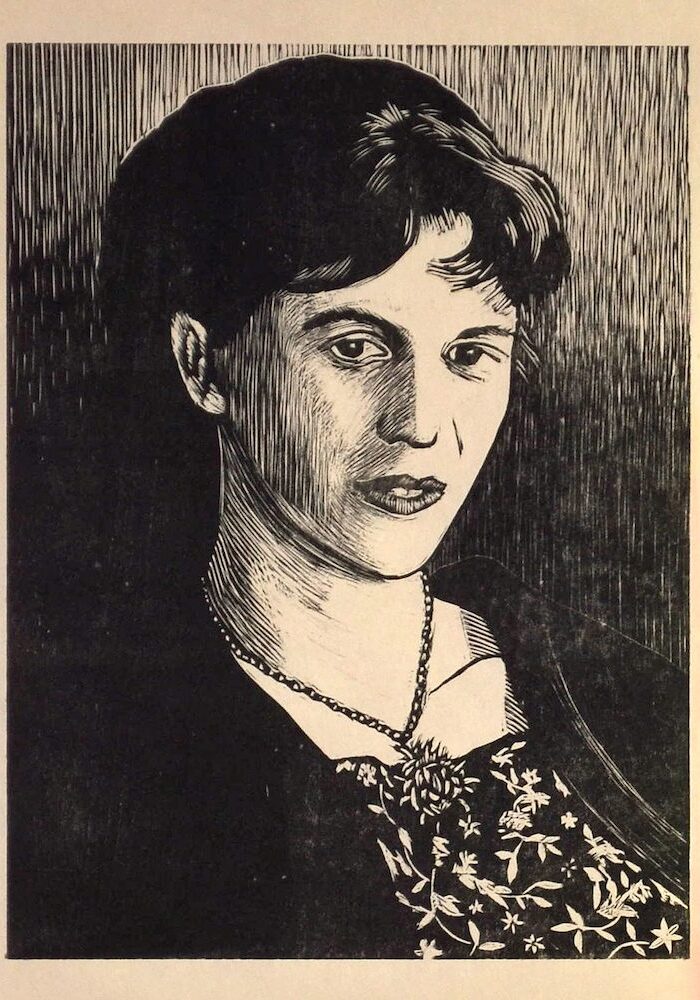

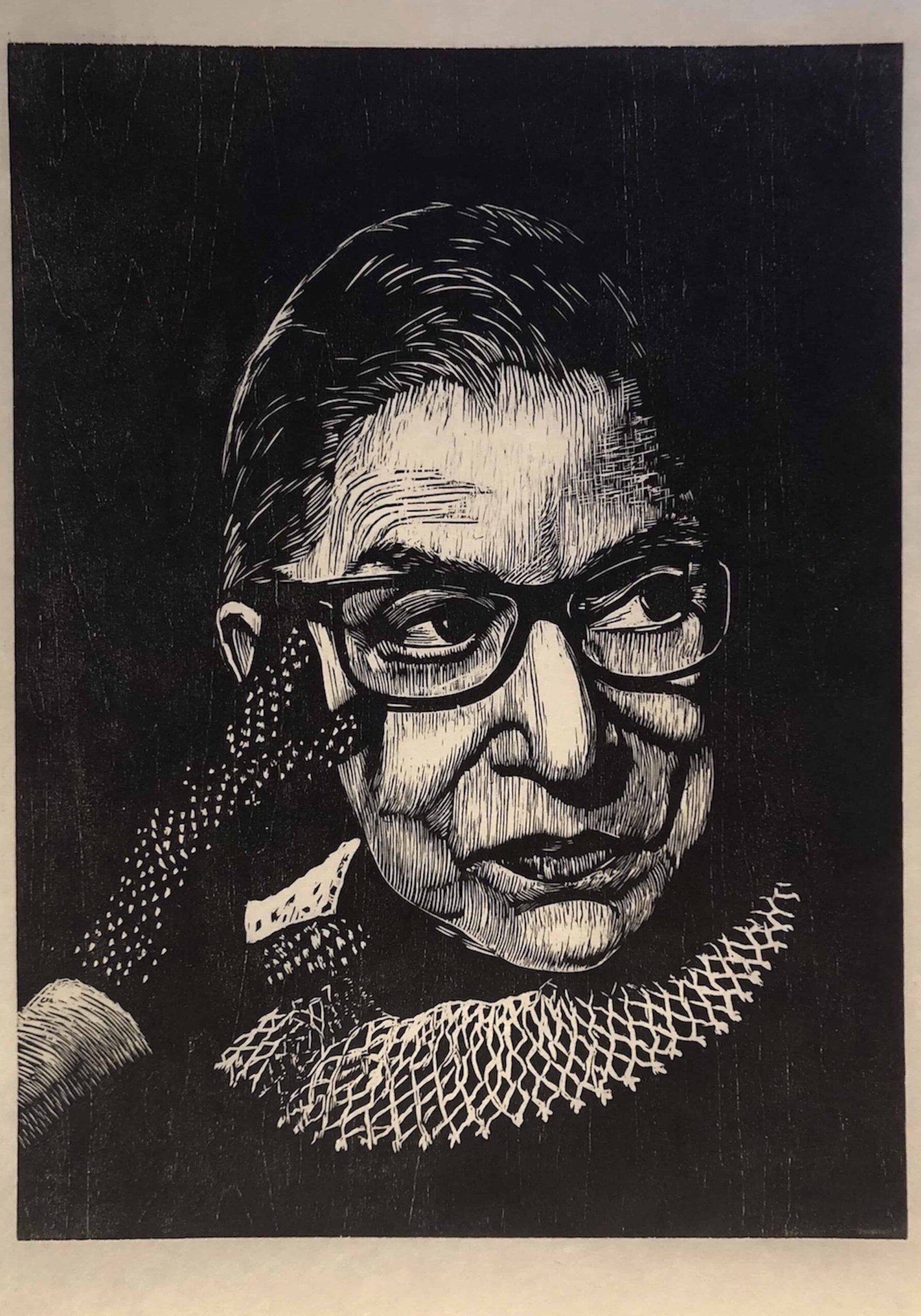

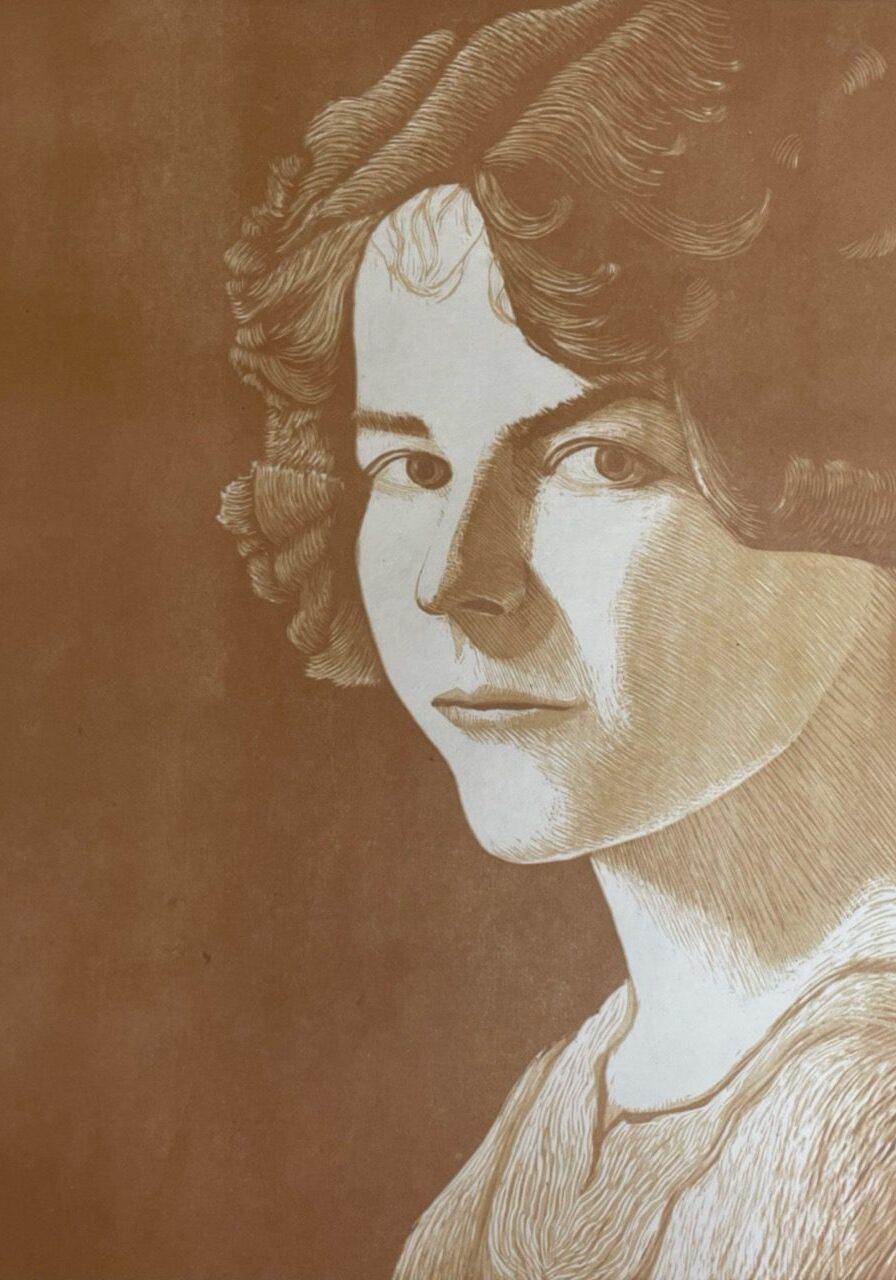

Woodcut of Sylvia

There are others in the series of photographs

the artist could have chosen. The one where her smile

is a cracked-open geode. Radiant. Or the one beside him

on the couch, her crown of thorns necklace partially

visible there too, Hughes looking like a tired old man.

Here, her armored jewelry is prominent, showing

she won’t shy from hard edges. She’s interior, but she’s not

looking at nothing. She’s just not looking at you, or me.

She’s training her mind’s eye to make miracles.

She is witch-magician, yet only thirty when she dies.

Still 1959 here, neither child born yet. Curl of girlish

bangs, crosshatch cheeks, cardigan, and briar patch dress

on which the nettle-like necklace makes it seem

she’s fastened a tidy explosion just below her clavicle.

Dangerous adornment, she’s a woman avoiding a gaze.

What can’t be seen is sea, rain, the slick rocks

of the North Shore, the insistence of blue skies and bulbs,

the exhaustion of spring, the incessancy of clouds.

Her brilliance is rooted there, in the formative spaces,

before nappies and milk mind. But not before poetry.

That was manifest in the salt-cured hometown,

the fierce mind admiring other gods, the heights to which

they understood expanse and wrote that way to match,

though she outmatched them all. Hairshirt necklace,

hairball amulet. Destined for domestic and divine.

Rebecca Hart Olander

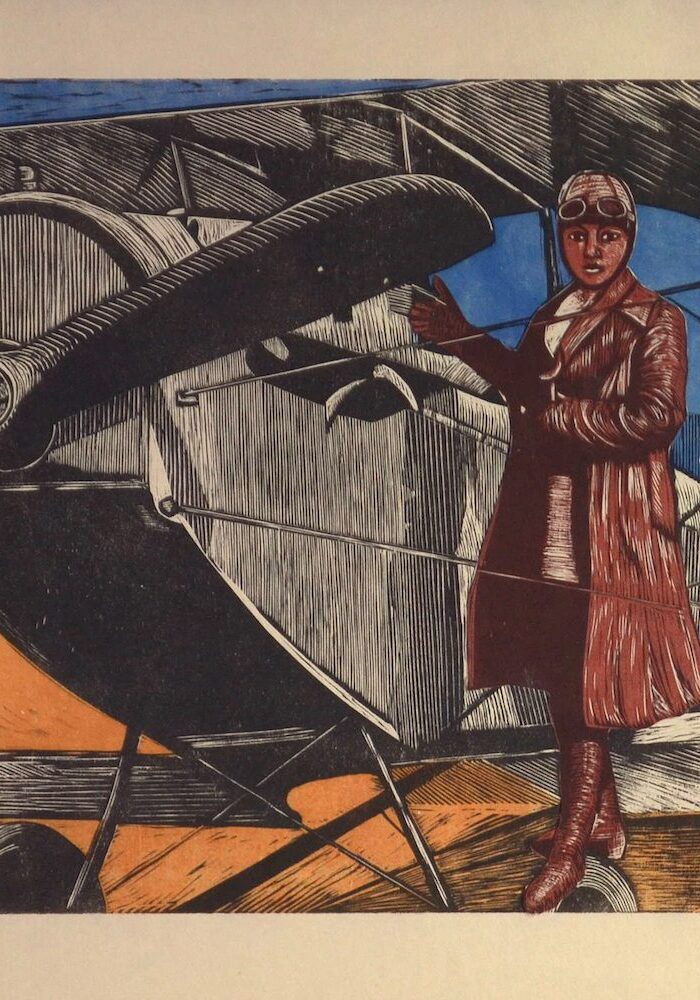

Queen Bess

Built for flight, for soaring, she who

always checked her wings, the weather—

aviatrix, wing-walker, barnstormer,

first black woman pilot in the U.S.—

heard the stories of WWI flyers at the White Sox

Barber Shop in Chicago as she worked doing nails.

The military selling surplus “Jennys” in the twenties

(she would own two). And yet, to earn her pilot’s license,

the sharecropper’s daughter raised in Waxahachie, Texas

had to leave the country, train in France. The biplane

mostly wings, no steering wheel, no brakes.

If you fly above the earth does the world look truer?

She flew figure eights, dipping and looping, stuntwoman

and guide of her sky-self, parting the blue—

the see-through clouds, fully licensed to operate.

Demanded blacks and whites enter the same front gates.

She was thirty-four the last morning.

You don’t need to look up the weather report,

it was said to be a wrench—jammed—that sent her Jenny

spiraling, nose-diving, past the future roundabouts

to be named after her, the flying clubs she dreamed of

the pilots flying low, dropping blossoms on her grave.

—Sharon Tracey

The Longleaf Pine Woman

— Caroline Dormon (1888-1971)

I have listened to the trees talk, later

than I longed. My ear was its own

stethoscope, I felt the pulse, I heard

the waters flow through xylem

in vertical rivers, emptying

into fireworks of deep-green

needles. Need grows deeper.

For so long, I’ve collected life

histories. I’ve walked the land

through Louisiana, parish to parish,

raised seedlings, felt the fire

of their roman candles. A longing

carried me as I toiled to save them.

It can take a long century to reach

the forest canopy where sprays

of needles watch the clouds

and stars. And no bed is finer

than a needled floor, no resting

place more welcoming, far

below the oval, open crowns.

Being resinous, pitch and gum

can save them from fire, and

skeletons of snag may recover.

But from the blade? For this I walked.

—Sharon Tracey

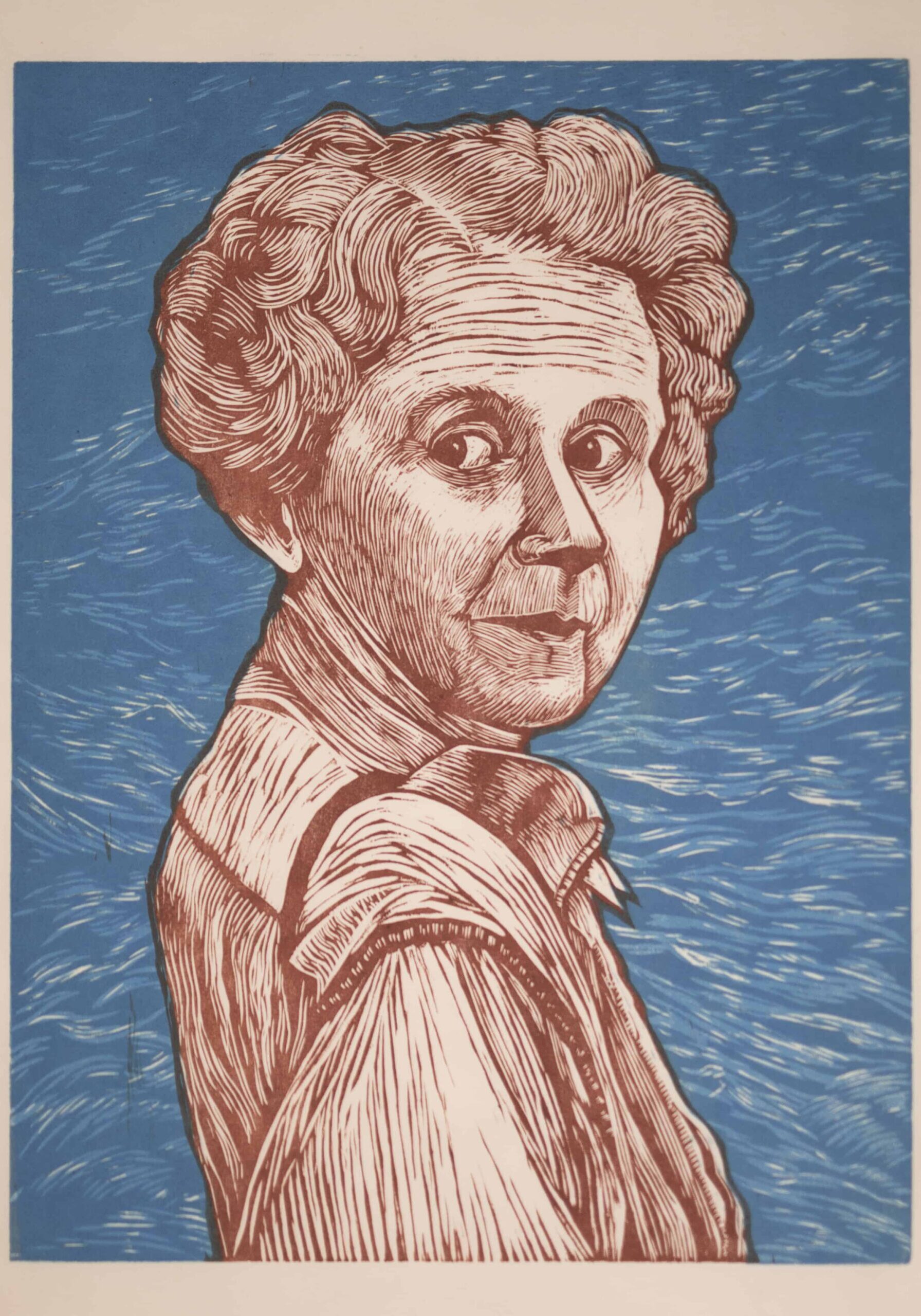

Thank You for Your Labors, Pioneer, Undertaken Often at Night

It is soothing, scientist, to think of the sand fleas,

and the ghost crabs that devour them, and the sea bass

that eat them, then the shark school circling,

and the remains of the fish tossed back in the jetsam

to the beach where the fleas flock to their food.

We can be comforted, deft lyricist, by your description

of moon-bewildered squid, how the swath of light

from the fullness finds them dashed upon the shore

in their panicked retreat, where the following morning

they serve as feast for scavenging gulls.

When we remember, beloved daughter, our own gone,

or you, by cancer, at 56, your mother might come to mind—

she typed your first manuscript to arrive famously without error

to its publisher—and we will know some things

can be managed by love and attention, and some can’t.

With your ode to ecology, Under the Sea-Wind, you urge us

to abandon human yardsticks, while the book itself survived

time’s ravages. You salvaged the original moldering illustrations,

forgotten in a warehouse in the midst of world war, to reprint

your masterpiece of sea, wind, migration, and change.

Rachel, you might be glancing backward at us

in our beautiful hell, driven not by fear, like Orpheus,

but by knowing we have not followed you into the sky or sea.

You could be draped in plumage splashed with cinnamon

and rust, like older sanderlings on their return flight.

You dwell in the shifting places, the microscopic,

the abyss. You knew it was our own folly, not any god,

that would trap us in the dark. Your eye, sharp

as a sandpiper rooting out a fiddler, took note. So many

tiny black journals. So many hours in the field.

You are in the tide pools. You are urchin, anemone,

sea star, mollusk, limpet, barnacle. You are algae, mussel,

and sponge, soaking in the beauty and wonder

and sharing it with us. The waters rise, and you cling

to the granite, to our conscience, our regret.

And despite altered terrain, the silenced season, it lulls us

to read what you left in your wake, protector of prairie

and ocean edge. How small a part we are in what there is.

How we should discriminate when we blanket earth and sea

with ourselves. To think it could still be as you say, the chain.

—Rebecca Hart Olander

HeLa: Stolen Gifts*

Henrietta (Hennie) Lacks

b. 8/1/1920 – d. 10/4/1951

She did not want immortality,

just life. Johns Hopkins, decades ago

cells pilfered, slashed from her cervix,

dropped onto clots of chicken-blood.

As they doubled each day; named HeLa.

Hennie, heartbeat of her clan –

bein' with her was like bein' with fun.”

Last goodbyes – her five children on

a small patch of grass as she sobbed --

pressed face, hands, to hospital glass.

Motherless days, months, years.

Daughter – longing – nails painted

fire-engine red like her mother's;

lifetime quest for answers. Son,

in fury, “Them cells were stolen.”

No permission given – “50 million

metric tons” grown and used in labs

worldwide. Family uncompensated.

We all have benefited: Gene mapping,

new chemos, vaccines – polio and COVID.

How do we thank you dear Hennie?

By Delores Juanita Brown and Janine Roberts

*With much appreciation to Henrietta's family for telling her story and theirs to Rebecca Skloot. All quotes and details are from the superb book by Skloot, “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks”.

I get you, Betty.

Convinced of our magnificence even in the silence.

When they played, “not you,”

we

sang “watch me.”

Even with yolk in our lashes.

Pieces of work ever lacking.

We wear the woven as a door but ache to trade

for a suit of skin.

Born in prison, we wouldn’t be caged.

Won’t be caught.

We’re determined

dynamic stubborn queer

biting brilliant

precocious

strange

unstable

uncertain

Lost

we yearn for personal truth connection clarity love peace exhilaration power strength speed

We tasted the crumbs

wanted the bite.

The nostalgia of

white knuckles on a wheel,

leaning into a curve,

controlling the machine.

Dominion over a landscape.

But we’re so shy scared tired safer

Alone.

—joj

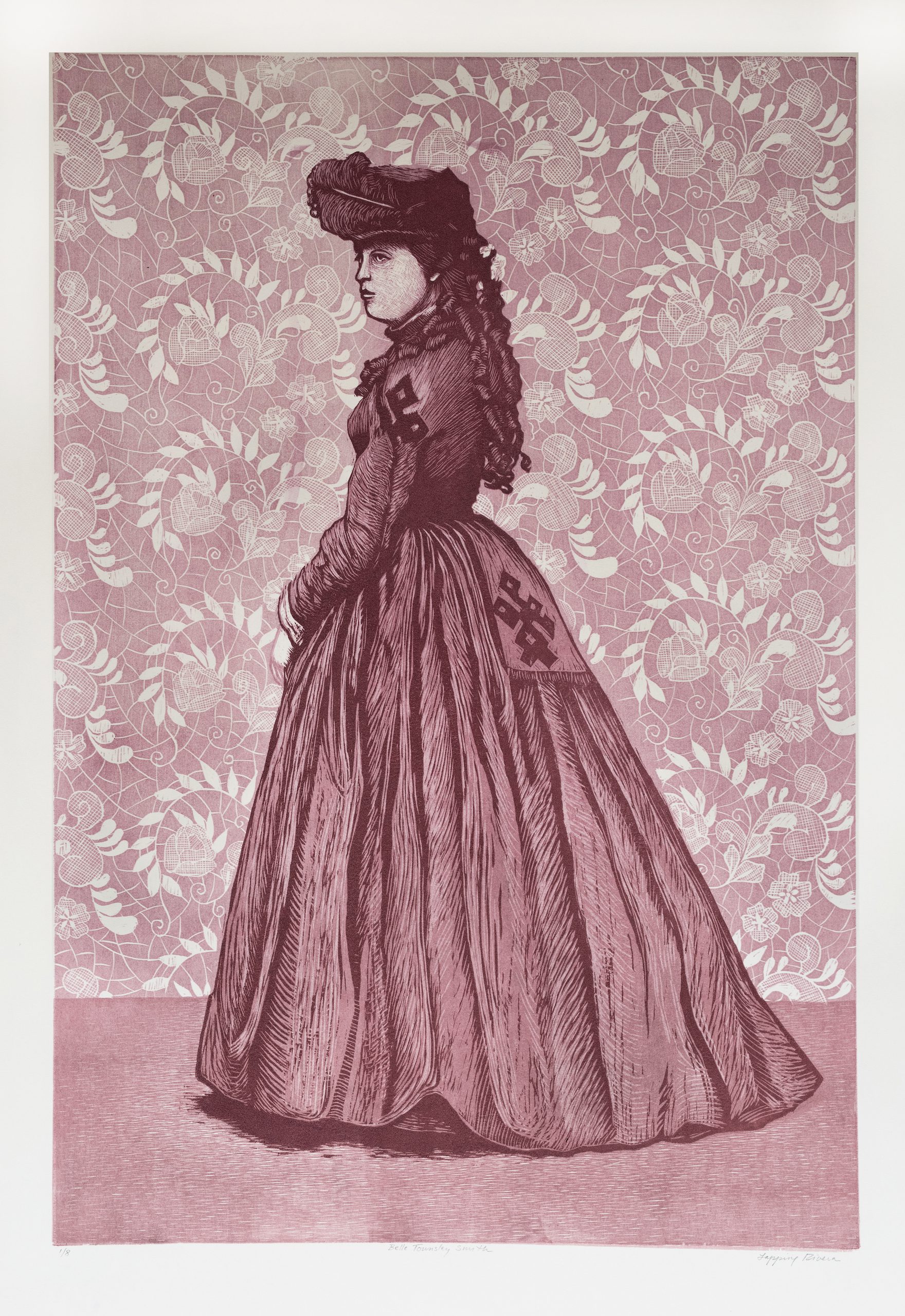

Belle Townsley Smith

(1845–1928)

Born and buried in Springfield

and co-founder of the city’s first art museum

named for her husband alone:

George Walter Vincent Smith Art Museum

See for yourself. It gleams above

the main doors.

Married in 1882, they set off for Europe

where two years of collecting turned into five—

tapestries, paintings, bronzes, ceramics,

illuminated manuscripts. Returning, they

offered the collection as a gift to the city

if they would build it a home.

Her passion was the art of lacemaking

and she sought out the finest—Italian cutwork,

Rose-point, Spanish, and French laces—

designed and handmade with needle

and bobbin, threads of linen and silk.

The lacemaker threading the eyelets,

the openwork web delicate and growing,

covering yet revealing. Creating veils,

shawls, and lappets—the lace strips

worn by bishops and popes or attached

to a woman’s hair in pairs. She organized

the museum’s lace exhibit in 1912 to fanfare.

Today, walking across the Quadrangle

and approaching the Pompeian brick façade,

it’s hard not to wonder if anyone suggested

one of his names be given up so one of

hers could shine. A legacy handed down.

After all, the museum was her child.

—Sharon Tracey

Legacy

by Dorsía Smith Silva

nestled within your mind

light unbranched

and shook out many

breaths to center women

across society’s core

women that came to you, dear doctor,

with their brown and Black voices shut

and choices battered

women that had sorrow

draped across their shoulders

until you extended the push

for women to have choices of their bodies

for women to say never again

to forced sterilizations as you

shaped guidelines to encrust rights

dear doctor, you spun hope

for those with HIV and AIDS

to unhide and cup compassion

like fresh pulses that stretched

throughout this world

from New York to Puerto Rico

and Puerto Rico to New York

your unbuttoned call for the island

to be free was built on the song

of the coqui and wish of the UPR

you carried Puerto Rico, dear boricua,

like hope within your chest

it rose every time you came

to where the community huddled

and injustices vanished

so much change became fulfilled by your fingers

and bloomed in various directions

you as the first Latina president

of the American Public Health Association

you with the Presidential Citizens Medal

so many galaxies that transformed from your touch,

dear boricua, so many equalities that lit up

because of your fearlessness, dear doctor,

so that even though cancer overtook your body

it has been impossible not to reflect your light

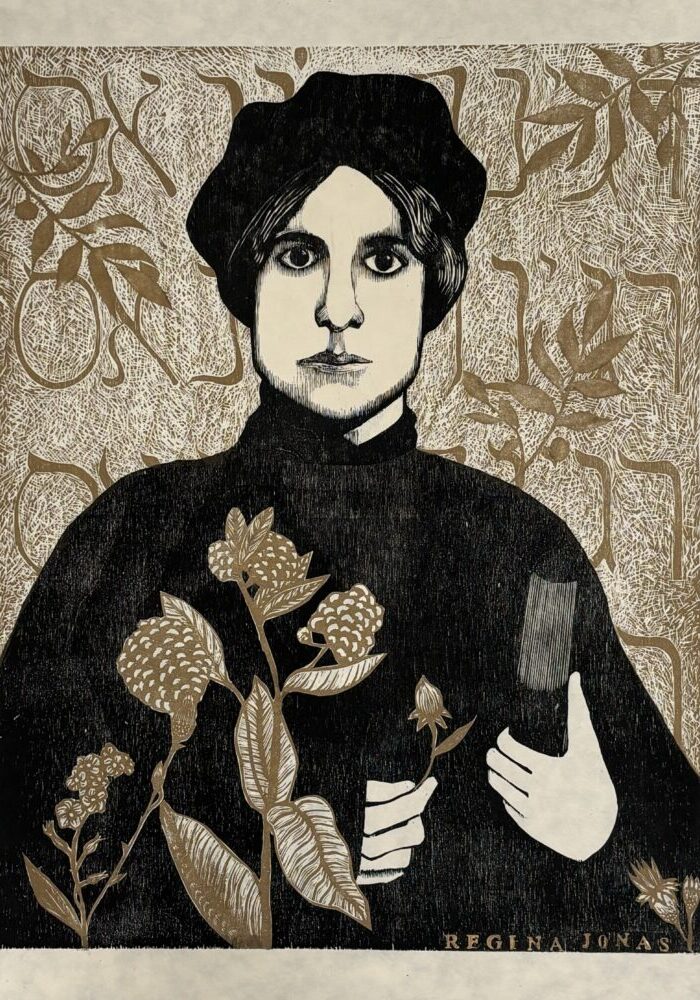

Why Regina Jonas Became a Rabbi

by Pamela Wax

Because God knew her name,

and she heard it called.

Because the lapis lazuli ceiling

was waiting for her,

God’s feet upon it.

Because Yalta had broken 400 jugs of wine.

Because Bruria learned 300 traditions

from 300 masters in a single day.

Because Yalta and Bruria were her mothers.

Because she was Sisyphean, rolling

her boulder up the mountain

again and again to gain purchase.

Because she was an ox,

stiff-necked, mastering the tools

of pilpul to gain entrance

to the master’s house.

Because she didn’t aim to dismantle it.

Because Europe was burning, her people

were wanting.

Because she could feed them almost 4000

years’ of falling down and getting up.

Because she didn’t fear death.

Because she loved

with all her heart, her soul, her might.

Because we—hundreds of us—

followed her footsteps, shards

of lapis lazuli in our soles.

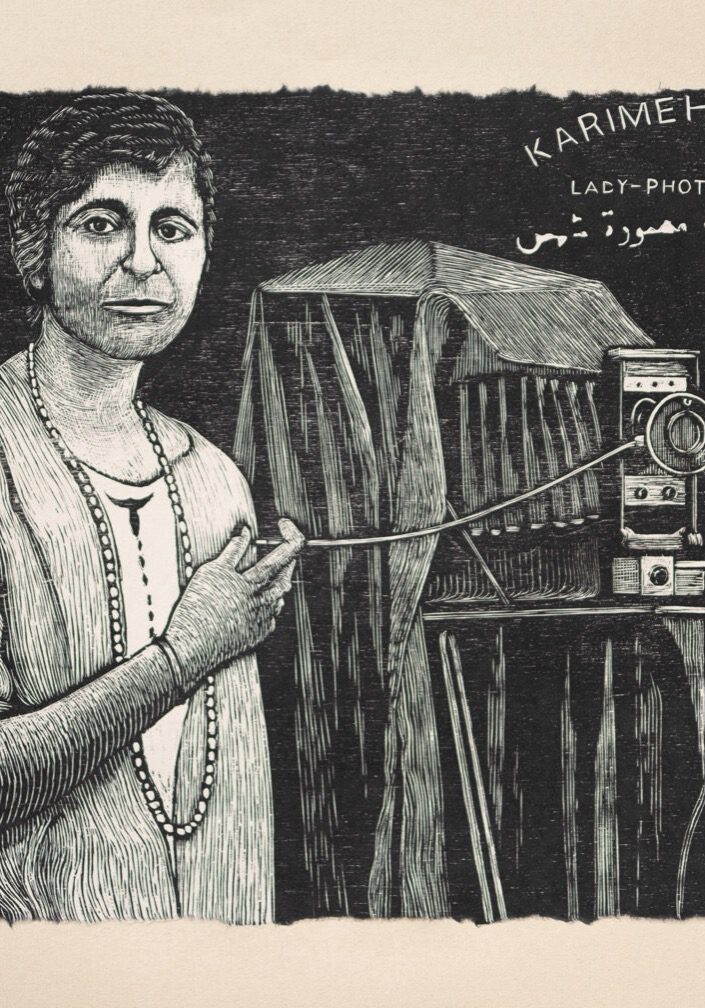

For Karimeh Abbud

by Priscilla Wathington

Yours was a world all in its place

your baby brother tucked into his mother's bed like Galilee

was tucked into her Palestine with that faraway look

in the eyes asking all those questions of the mustache

and the dove-necklaced dusk,

the organ-cooing night.

There you are in that unshaken globe

rising so light can find your arms

moving furiously toward the secret chamber

of your camera. At seventeen, you looked where I looked

and saw Bethlehem painted slick with pink

and soapy whites. No reenactors were hired

that morning. The birds woke and found a sesame candy bar

teeming with larvae. A shopkeeper's sleeves danced with pine

-pricked light as he wiped the dust off a cup.

Nothing held still but your finger choosing

where to freeze the hour: 1919 Palestine

a silver life. Yes, we were acrobats

standing on a bottle-propped chair,

shy young mothers of peach

-cheeked babes with fine thread

along our hips, yes,

we were peasants memorizing

the beetles of the fields, old men breathless

among Sebastia's columns, we were crowned

Miss Palestine of Akka with pearls down to our waist,

and we were bare-footed teens

pulling water from a Nazareth

well, with a half-smile and a palm to shade our eyes,

yes, we were that perfumed city

kid, briefly immaculate, for you,

our lady, our national photographer.

But time rushed in and when you took another picture,

your baby brother had fallen from the bell tower

and there were soldiers grabbing a shopkeeper by his sleeves.

And when you looked again, Zionists were photographing

the plains, plucking postcards

from apartments. Oh photographer of the sun

after your death, we knocked on the water tank

and suffocated among smugglers.

Still, your camera returns us

tall and tan to our towns and our farms.

Oh we are the land’s

lavish fruits.

***

Poem Note: The lines “after your death, we knocked on the water tank /

and suffocated among smugglers” are in conversation with Ghassan Kanafani’s Men in the Sun.

***

Karimeh Abbud Bio:

Born in 1893 to an educated Protestant family in Bethlehem, Karimeh Abbud's life spanned a critical juncture of Palestinian history, from the Ottoman to the British Mandate periods and the arrival of growing numbers of European Zionists. Against this backdrop, Abbud carved out a place for herself as the first "lady photographer" of Palestine, setting up multiple photography studios, and running a successful commercial and portrait business. She often photographed Palestine's urban, bourgeois families inside of their homes and is also known for her postcards of landscapes, landmarks and everyday activities, creating a rich record of Palestinian life during this period. There is some debate about the date of her death from tuberculosis, which scholars place between 1940 and 1955. In the aftermath of the Nakba in 1948, when approximately one million Palestinians were expelled or displaced from their homeland, much of Abboud's oeuvre was plundered and is still held today in private Israeli collections.

Selected Sources:

Mrowat, Ahmad. "Karimeh Abbud: Early Woman Photographer (1896-1955)."

Jerusalem Quarterly, Issue 31, Summer 2007. Institute for Palestine Studies,

doi: 10.70190/jq.I31.p72

Nassar, Issam. "Early Local Photography in Palestine: The Legacy of Karimeh Abbud."

Jerusalem Quarterly, Issue 46, Summer 2011. Institute for Palestine Studies,

doi: 10.70190/jq.I46.p23

Raheb, Mitri. "Karimeh Abbud: Entrepreneurship and Early Training." Jerusalem

Quarterly, Issue 88, Winter 2021. Institute for Palestine Studies, doi: 10.70190/jq.I88.p55

Priscilla Wathington Bio:

Priscilla Wathington is a Palestinian American poet/editor and the author of the chapbook, Paper and Stick (Tram Editions/2021). Her poems have appeared in Prairie Schooner, Four Way Review, Gulf Coast, Michigan Quarterly Review, and elsewhere. She was the Sam Mazza Writer in Residence at San Francisco State University’s Poetry Center in 2024 and a Tin House Winter Workshop Scholar in 2025. Wathington sits on the board of the Radius of Arab American Writers (RAWI) and holds an MFA from Warren Wilson College.

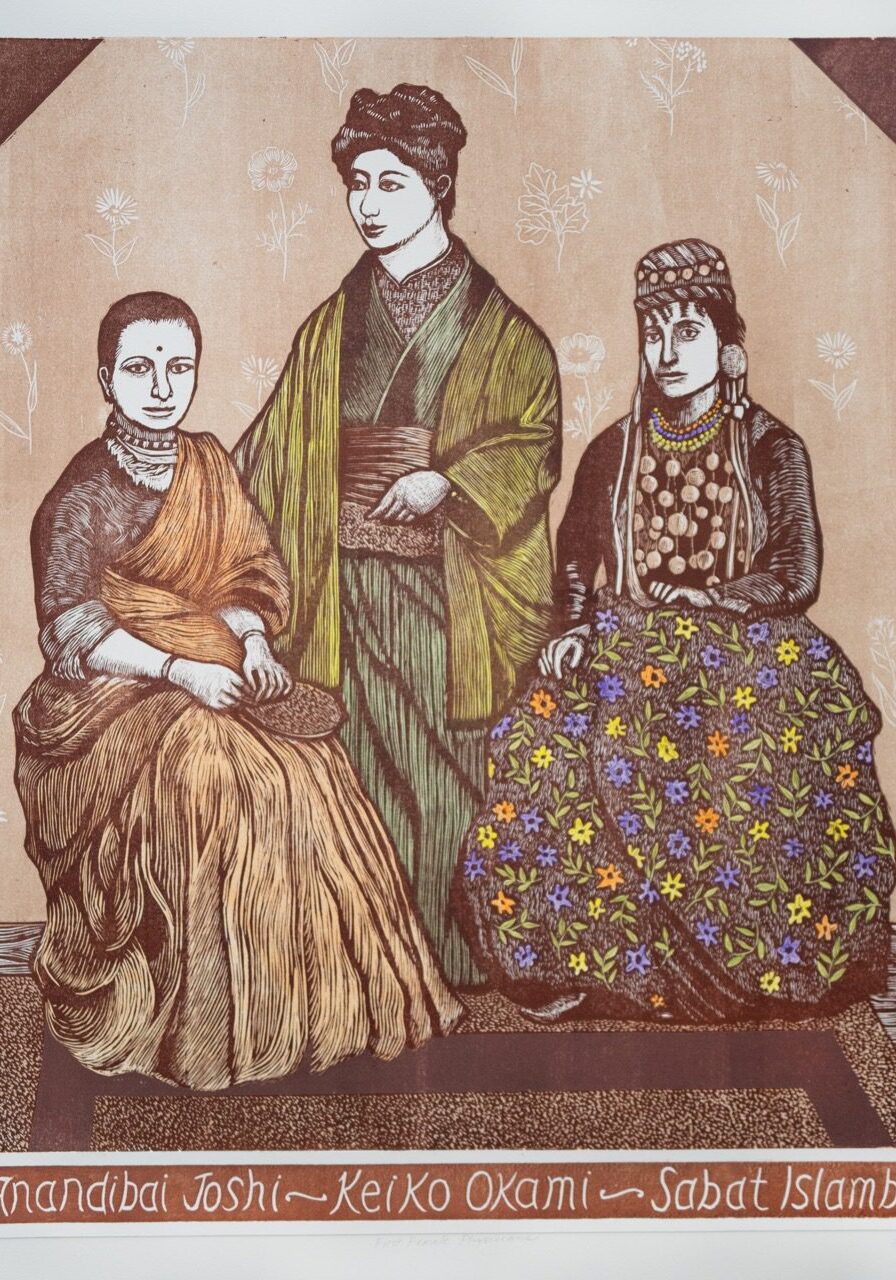

Dean’s Reception, Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, October 10, 1885

Dr. Anandibai Joshi (class of 1886)

Namaskar. My tree is the mango, my season spring, my favorite garment not my sari but a white lab coat. The need for female doctors in India runs deep, and I dedicate myself to become one. Married off at nine, mother at fourteen, my newborn son lived only ten days. Where was medical care for birth and the afterlife? What is the end of earthly suffering and pain? What fuel to light a fire, sail across two oceans! I who knew no English learned. Feverish, breathless, determined. Arrived in a new world so I could return to treat mothers and a country’s children in mine. Bind ancient practices to modern medicine. Had I survived to reach my twenty-second birthday, you could have found me—physician-in-charge—at Edward Albert Memorial Hospital in Kolhapur. Maybe

I could have found a cure for the tuberculosis that killed me.

Dr. Keiko Okama (class of 1889)

I’m looking off into the distance, thinking of the resilient ginkgo back home ready to turn yellow-gold. Under my kimono—my body, my twenty-four ribs born in Tokyo. My brain full of medical questions, my heart a pulsing metronome, my stethoscope ready to listen to womb and lung. We women will break through the fear of many things—hysteria, neuralgia, uterine disease. Follow the facts through anatomy, histology, pathology. Feel the weight of first Dr. in front of our names, first foreigners. I will return to Japan and open a clinic. My visage serious, body and mind wanting more. No seer here to reveal who will soon die tragically, who will slip into history with scant trace, who will open the doors of a women’s hospital and school of nursing. Hard won unity of three who will know more than our share of death, but also life. Call it serendipity, call it destiny. Call it one small cure, a spark.

Dr. Sabat Islambuli (class of 1890)

It is too warm for these formal clothes today, my kaftan embroidered with a traveling garden, my hat ribboned with coins. I’m daydreaming of home—apricots in sun, rain shadows hugging the mountains, fragrant jasmine, the light of Damascus.

Also of materia medica, medicinal herbs for remedies and possible cures. One day I will return to Syria. After the textbooks and lectures, physiology and obstetrics, blood and bones, the stanch and stitch of wounds. With instruments for my very own black bag—syringe and needles, scalpels and auriscope, bandages and spirit lamp. I am sorry to leave few tracks, but keep faith that hard work and perseverance made me a servant to community. To be lost in the world happens to almost everyone. To be noticed by history is something. Even in one found photograph, one woodcut portrait inked by an artist. In this way, we are alive.

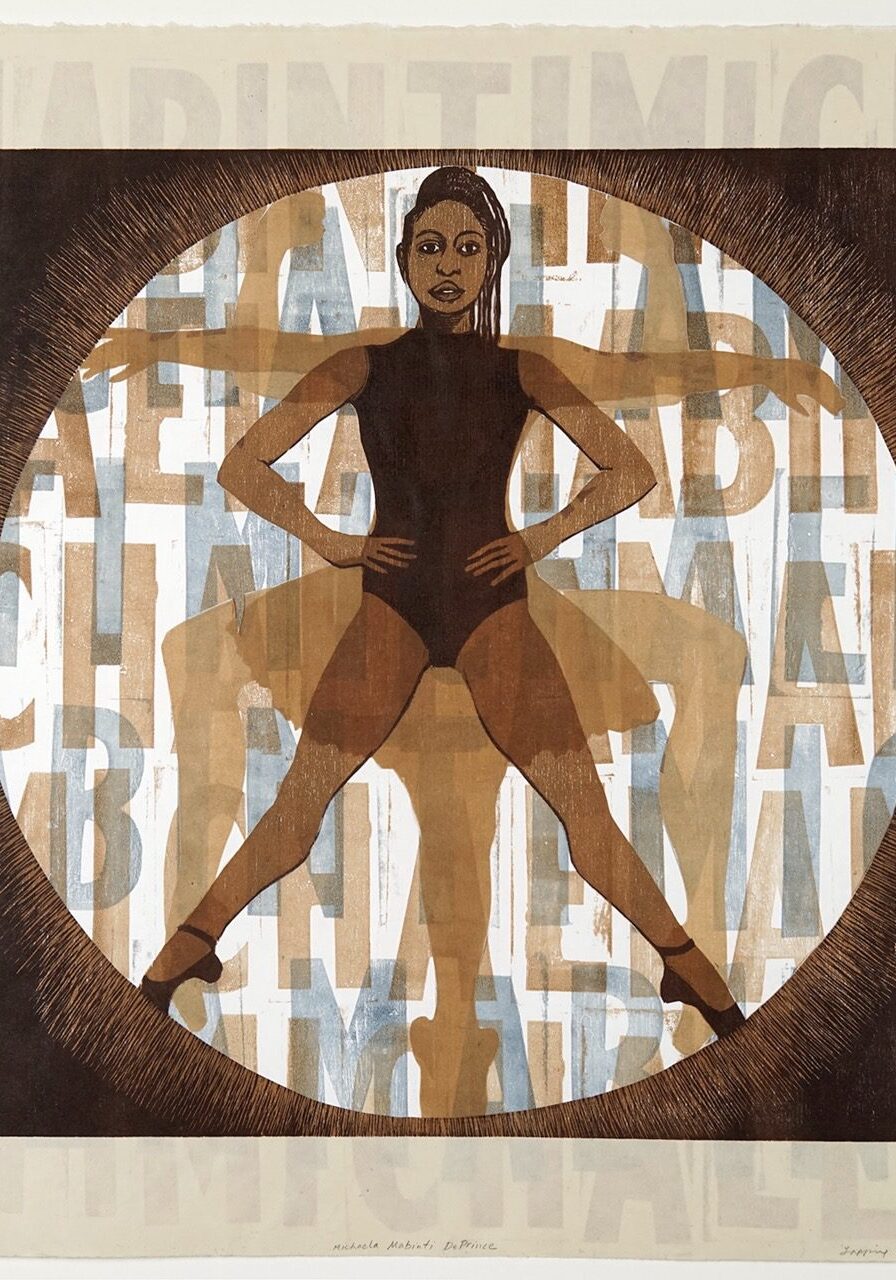

When I danced

by Lisbeth White

-For Michaela Mabinty DePrince

I danced for a miracle

or maybe the dance was a miracle

or maybe

I was

that my limbs could become a fury

swans light on the water

that I could stretch my leg

all the way to heaven

balance & bend like the cotton tree

never break never shatter

always I was free/d

let me dance again

for miracles

let my body be the body

that summons them

may they cascade down

this heaven-stretched leg

back here to this earth

save another child too